Cash. Bonds. Equities.

- dthenry5

- May 15, 2024

- 5 min read

On my first day in my first job in the City, I was taken into a side room by our Head of Investment Research to get a walk through on the basics of investing.

I had originally been hired to work in compliance, and had a legal rather than a financial background. Knew less than nothing about the markets - didn’t know what a stock was, didn’t know what a bond was. With hindsight, maybe even the “basics” were a little challenging for day one…

Anyway, one of the topics that we covered that day was the importance of portfolio diversification. The ultimate goal for the rational investor, it transpired, was to achieve as much return on her money as she could for the risk that she was taking. Ensuring a properly diversified portfolio provides the primary means to this end.

Now we've had a wee chat about risk in the past you and I, specifically the main kinds and the ones that I believe that investors should concern themselves with. But for the purposes of today’s post when I refer to “risk” I mean volatility - the day to day swings in value that your investments experience.

Most of the time, when the pros talk about risk, they mean volatility. And this can occasionally lead to misunderstandings with clients but that’s a whole other conversation.

Anyway, back to the rational investor. She recognises the long term growth offered by global stocks, and she understands that “losses” in the equity market as a whole have always proven to be temporary with the benefit of hindsight, as markets have always returned to their permanent advance in due course. Nonetheless, she concludes that she wouldn’t be able to cope with her investments (temporarily) declining by half of their value at some point in the future.

This being the case, we cannot invest the entirety of her portfolio into stocks. So what are our alternatives? What other assets can we add to the portfolio to offer her some diversification?

The classic answer is provided by bonds. Bonds have historically offered diversification to stocks, most crucially during those periods that I allude to above when equities are like your uncle at Christmas - they are getting properly hammered.

The below table shows the calendar year returns for the MSCI All Country World Index (the global stock market) and the Bloomberg Global Aggregate Bond Index (the most commonly used index for global bonds), going back to 1990.

Rather imaginatively, years where returns are positive are shown in green and negative ones are shown in red.

From the beginning of 1990 bonds have posted positive calendar year returns 91% of the time. Stocks, slightly less at 73.5% of the time.

But, and this is the important bit, when stocks have done poorly bonds have mostly been there to pick up the slack. In fact, in only two of the thirty four calendar years shown have bonds and stocks both posted negative returns - 1994 and 2022. On the vast majority of occasions, one or both, have done well.

2022 was a poor year for stocks, and a dreadful one for bonds. While equities regularly go through periods where they fall by 10%+ in value, bond investors do not sign up to experience 10% drawdowns all that often.

Also consider that gilts (UK government bonds) did worse than the globally diversified Bloomberg index used above, and index linked gilts did even worse again.

Source: Dimensional. All returns are shown in Sterling terms.

For bond investors, and particularly those based in the UK, 2022 was their annus horribilis.

Recency bias is a psychological bias that causes us to assume that recent events are more likely to recur in future. Also known (by me) as “short memory syndrome”.

With the bond market going through this historically bad run just a few short years ago, many analysts have been taking the opportunity to say that you won’t be able to rely on bonds to protect you against equity market falls in the future. That 2022 marked the beginning of a paradigm shift.

When we read such comments, it is is important for us all to bear in mind that everyone has something to sell. Often, these analysts work for large investment institutions that manufacture products that are designed to offer an alternative to boring old bonds and equities. And these “alternatives” are invariably more expensive than traditional asset classes.

The City makes little to no money out of a simple 60/40 equity and bond portfolio - access to this for the end investor has become entirely commoditised. So the industry has a duty to convince you that complicated is better, and flog you whatever “alt” is rolling off the conveyor belt this week.

Structured products, derivatives, absolute return, trend following, macro strategies - you don’t need any of this stuff to build wealth. But you’ll have it shoved down your throat anyway because that’s where the margin is.

I am of the view that a portfolio composed of cash, bonds and equities is perfectly able to get almost everyone to where they need to go.

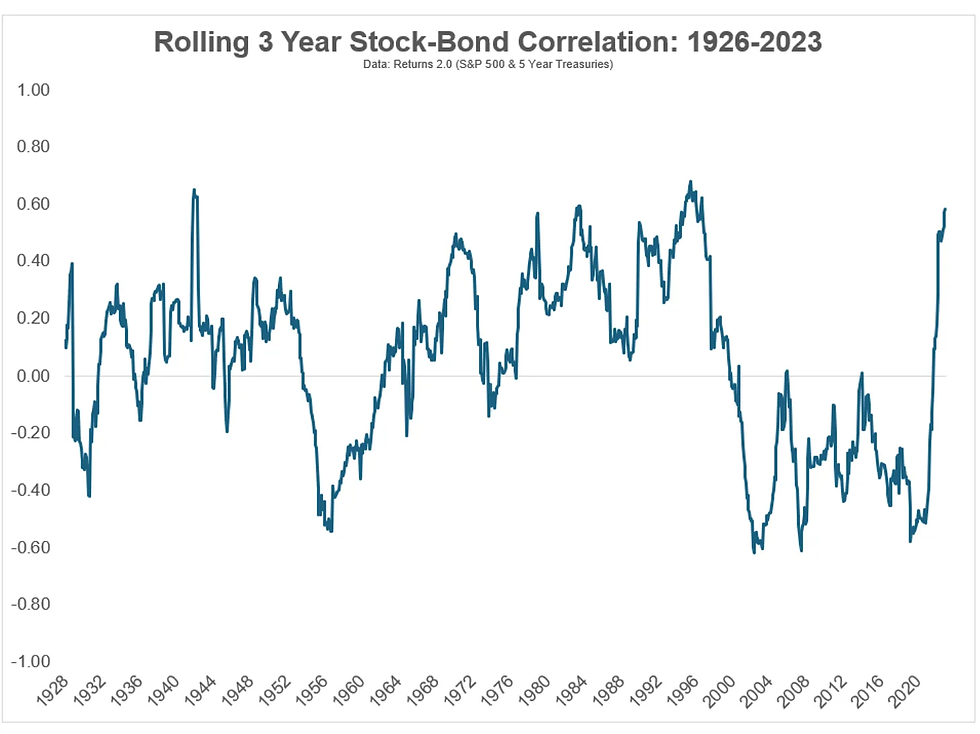

Since the beginning of this century, the correlation between bonds and equities has almost always been negative. As we can see from the below chart, this trend reversed massively in 2022 when both stocks and bonds sold off together.

Source: Returns 2.0, via the brilliant Ben Carlson at A Wealth Of Common Sense.

But bonds and stocks exhibiting a higher correlation is not in and of itself a reason to abandon a bond/equity allocation.

As you can also see from the above chart, from the late 70’s through to the year 2000 bonds and stocks were positively correlated - and during this period a 60% stock/40% bond allocation did just fine.

Source: MSCI & FTSE, via FE Analytics. Returns are shown on a total return basis, in GBP. I have used US treasuries for the bond component of the portfolio, as the data for the Global Aggregate Bond index doesn’t go this far back.

We don’t need bonds to be uncorrelated to equities all of the time, most of the time equities are working just fine. From a diversification perspective we just need bonds to work when stocks are falling and the good news is that in the past, most of the time they have done just that.

The biggest and deepest drawdowns for equities tend to take place during recessions, and during recessions investors crave return of capital, rather than return on capital. Bonds offer this safety.

During recessions we also see that interest rates almost invariably fall. This causes bond prices to rise, and (partially) offset the falling value of the stocks within your portfolio.

Admittedly there are times where bonds haven’t bailed you out, typically during periods of inflationary shock like we saw in 2022. But such instances have proven to be the exception rather than the rule. Just because we had one recently doesn’t mean that this is necessarily the new norm.

And anyway, isn’t an investment strategy that works most of time good enough? What are we actually trying to achieve here?

There is no such thing as a perfect investment strategy, and all of us must accept that there will inevitably be compromises involved in any approach that we take.

Sure, we can attempt to refine our portfolios to an increasingly optimum standard - but perfection is unattainable, life doesn’t happen in a laboratory and ultimately none of us have a crystal ball. We are all just making our best guess.

The data that we have seen provides evidence that for most individual investors (you and I) a simple approach is perfectly fine.

Cash to meet your short term needs;

Global equities to provide the engine of growth; and

High quality bonds if you can’t live with the implied volatility of a 100% equity portfolio (most people close to, or in retirement, can’t).

Next week, further to the above, we are going to have a look at how much cash I believe that someone in retirement should hold as part of their overall asset allocation.

Comments